Why You Should Read KGB Literati

An Elevator Pitch for My Book

In July 2025, British journalist Charlie English published The CIA Book Club, a book about a CIA undercover program to smuggle Western literature into the Communist countries of Eastern Europe. The program aimed at breaking the Communist regimes from the inside by stimulating free and open thinking. It worked. Free thought successfully moved authoritarian mountains. The Communist Eastern Europe ceased to exist.

English’s book focused mostly on Poland, today a Western-style democracy, but what about Russia which generated the Communist political system with the Bolshevik revolution in 1917? After a decade-long flirt with democracy under President Boris Yeltsin, Russia has again taken a decidedly authoritarian path under the direction of his successor, former KGB officer Vladimir Putin. At this time, it is one of the most repressive regimes in the world. Why did “free thought” fail there?

My book KGB Literati argues that the book publishing legacy of the KGB, the powerful Soviet state security organization, played a crucial role. KGB had an ideologically different, diametrically opposed mission from the CIA. It aimed not to promote free and creative thinking, but to project a particular view of the world and shape the hearts and minds of the Soviet public accordingly.

KGB wanted books that exaggerated the positive impact of its activities and glorified its self-perceived victories against its Western antagonists framed as malevolent and decadent. It directed, organized, and funded its own active and retired officers to take a part in these literary counterintelligence efforts. I call these officers “KGB Literati” and they are the main protagonists of my book.

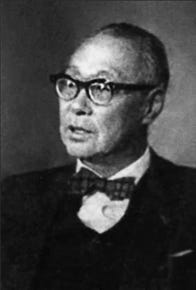

For instance, a veteran Soviet counterintelligence officer Roman Kim sought to erase the gains of the CIA Book Club by writing spy fiction novels to rival the British writer Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond. Kim’s novels are set in locations ranging from Asia to Europe and from North America to Africa. What ties them together is the plot pattern in which Soviets or their allies always win and the West always loses in the end.

Or consider Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina, one of the highest-ranking women in Soviet intelligence in the 1940s, whom some have seen as a prototype for Ian Fleming’s Rosa Khlebb from his spy classic From Russia, With Love. In Voskresenskaya-Rybkina’s spy fiction centered on the Bolshevik conspiratorial activities against the Russian Tsarist regime, Vladimir Lenin, the founding father of the Soviet Union, is endowed with the skills and abilities of a James Bond-type figure. Without women and alcohol, of course.

There is also KGB Lieutenant General Oleg Gribanov, the head of Soviet counterintelligence from 1956 to 1964, who developed a prominent second career in spy fiction writing after he was fired from his job. His co-authored novels about Soviet counterintelligence successes against Western agents infiltrated into the Soviet Union were turned into blockbuster Soviet films. According to defector testimony, these films are still used as teaching tools in Russia’s security and intelligence academies.

Kim, Voskresenskaya-Rybkina, Gribanov, and numerous others, with similar backgrounds, make up a cohort of KGB Literati on the pages of my book. They all had the greater glory of the Soviet state and the KGB as the primary objective in their fiction.

And they appear to have achieved that objective in the hearts and minds of many of their Russian readers. Even in the relatively liberal 1990s, public opinions polls in Russia have consistently registered a high level of trust in security and intelligence officers.

We even have evidence from the “supreme leader” himself. Vladimir Putin proudly proclaimed in an interview: “My notion of the KGB came from romantic spy stories. I was a pure and utterly successful product of Soviet patriotic education.”

In other words, notwithstanding CIA efforts, Western decisionmakers have downplayed, or even ignored, the contributions of KGB Literati to Russia’s national identity construction at their peril. My book brings them out of the shadows for all to see. And take action.

Looks interesting!

Do you know if those novels are available somewhere translated to English?

Your book looks fascinating! I'm going to have to acquire a copy!